CuriosiD: The History of Detroit’s Water Works Park

Annamarie Sysling November 6, 2014As part of WDET’s CuriosiD, Anna Sysling answers listener Barbara’s question about the Detroit water park’s history

In this installment WDET’s Anna Sysling answers a question that was asked by listener Barbara Williams:

“I’ve always been fascinated by Water Works Park on Jefferson, What is its history? Are tours available?

To find the answer to Barb’s question, I spoke with Dan Austin, who runs HistoricDetroit.org and works for the Detroit Free Press. He knows a lot about Detroit’s historic locations, including the Water Works Park.

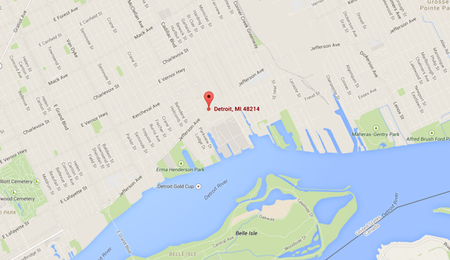

Detroit’s Water Works Park opened in the 1800s. At the time, very few cities in the United States had waterworks systems, but as Detroit’s population continued to grow, it became clear that the city needed a solution. After opening and closing two other waterworks systems in Detroit, the City Waterworks purchased 56 acres of land on East Jefferson near Cadillac Blvd, just east of Belle Isle. The plant was fully operational by 1879.

However, what’s most interesting is about this plant is that it offered Detroiters so much more than water.

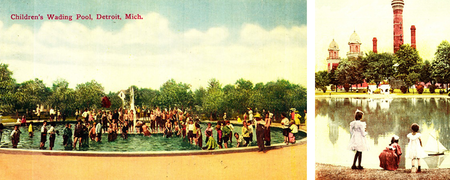

“There were [about] 100 acres of green space with swimming pools and picnic areas, playground equipment and you could take rowboats through these canals. It was a real leisurely spot much like Belle Isle was,” Austin says of the park.

Additionally, there were landmarks at the park that became tourist attractions in their own right. One of the primary attractions, the Hurlbut Memorial Gate, still remains today. Austin says the gate was built to honor longtime President of the Board of Water Commissioners, Chauncey Hurlbut. “When he died in 1885, he left his estate to the beautification of Water Works Park and part of that was to build this massive memorial gate,” Austin says of Hurlbut’s legacy.

There was also a flower clock at the park that was made completely of plants (excluding the hands and numbers on the clock), and was powered by water pressure. When the park closed, the clock was moved to Greenfield Village and was eventually returned to the city and placed at Belle Isle where it still remains.

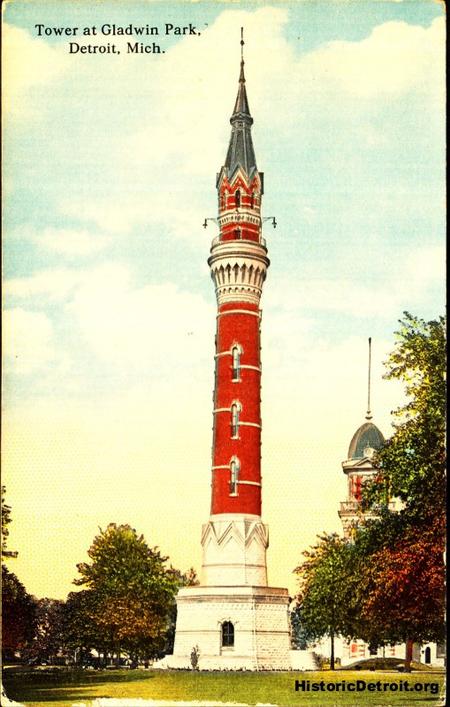

However, perhaps the biggest attraction at the park was the Water Works Tower. “It was a giant tower, 124 feet in the air and it looked kind of like a minaret. It doubled as an observation tower,” where Austin says park visitors could climb up to the top and look out. And in 1876, Austin says it was essentially the tallest thing in town at the time.

The tower was operational until 1895, which is around the time technology rendered it obsolete. However, for decades after, it still remained an iconic symbol of Detroit until it was brought down around 1945.

The city’s Buildings and Safety Engineering Department determined it was unsafe and too expensive to repair, after it went unmaintained throughout the park closures during World War I and World War II. The park was closed during both wars (and later on for the duration of the Korean War as well) because of those national security concerns.

While we might not necessarily think of Detroit as a target for terrorism today, Austin explains that during the World Wars, Detroit was the Arsenal of Democracy and was considered a prime target for enemies who could try to poison the city’s water supply.

At this point, it’s also important to remember that the Belle Isle Bridge didn’t exist when Water Works Park first opened. So, for many Detroiters not affluent enough to take a ferry to the island, Water Works Park was the place to go in Detroit for a relaxing afternoon.

After the first Belle Isle Bridge burned in 1915, a replacement bridge (the one that still exists today) was built in 1923. So, while Water Works Park was closed due to national security concerns, it was simultaneously becoming easier for people to get to Belle Isle, which eventually became Detroit’s premier recreational destination.

In addition to the tower being taken down, the lagoons were filled in after they were deemed unsanitary. There was some public outcry in the 1960s, and for a time a small part of the park was re-opened, but it just wasn’t the same.

“One by one, all these things that drew people to Water Works Park were taken away and eventually the park was taken away itself,” says Austin, and “if it wasn’t for the Hurlbut Memorial gate, people would be zipping by it on Jefferson without any indication that there was ever a park there.”