Grand Bargain: Early Payments Shift Investment Burden to Pension Funds

With the DIA, state making early payments in grand bargain, Detroit’s pension funds assume more risk.

“The onus is now on the retirement systems,” City Finance Director John Naglick.

During the city’s bankruptcy case, the “grand bargain” was described as an $816 million infusion of money to the city’s pension funds over the next two decades.

But for the two retirement systems to actually realize that amount – and use it to pay thousands of retirees – it is now even more dependent on how their own investments perform over the next 18 years.

That’s because the Detroit Institute of Arts recently prepaid much of its $100 million obligation after the state did the same last year under terms allowed by the bankruptcy settlements, specifically the grand bargain. Both the state and the museum realized discounts for the payments because of the “present-day valuation” provisions used to calculate them since they were made early.

“Anyone who has a mortgage understands that,” says Laura Bartell, a Wayne State University law professor specializing in bankruptcy. “If you borrow $100,000 to buy a home, you know that you are going to pay the bank far more than $100,000 over the years to pay back the loan. This is just the reverse of that. It takes the total amount being paid back and reduces it by the interest factor to present value.”

For the city’s two pension funds, the difference between the state’s and DIA‘s 20-year pledges and the early payoffs represents 6.75 percent reductions calculated annually, or roughly $191 million less than the grand bargain’s terms as discussed during the case, according to financial documents and sources.

The state’s reduction was about $155 million while the DIA’s to date is about $36 million.

That raises the stakes for the city’s pension funds. Instead of receiving $5 million annually for 20 years from the DIA, they already have most of the money they’ll get from the museum’s pledge.

Hear Detroit Finance Director John Naglick: “So now the onus is now on the retirement systems to earn 6.75 (percent). Any year we don’t is a year that we would have been better off waiting for the full payment.”

Future Earnings?

No one can predict how the markets will perform over the next two decades. If the returns on pension investments are greater than the 6.75 percent discounts, the systems’ gain from having the money now. If the fund investments yield lower returns, the annual payments would have been better for the systems.

Hear Police and Fire Retirement System Spokesperson Bruce Babiarz: “I probably wouldn’t use the word gamble. We have institutional investors, and this is a very complex, broadly diversified portfolio. They’re being very smart about the investments. It’s really dependent on a large part of the returns yielded on the stock and bond market.”

The two funds have roughly $5 billion in assets: $3 billion in the Police and Fire Retirement System and $2.3 billion in the General Retirement System. Together the funds pay out about $658 million annually. The Plan of Adjustment, the city’s blueprint for exiting bankruptcy and managing its finances for a limited amount of time, also uses a 6.75 percent return on pension investments for economic forecasting and the city’s fiscal planning.

But last year the city’s pension fund investments earned little or nothing in interest income.

Final audits are not complete, system officials say. But the PFRS may have gained or lost up to 1 percent, according to Babiarz. The GRS had a 2.6 percent yield, says spokesperson Tina Bassett.

Hear GRS Spokesperson Tina Bassett:“It’s always a concern when we don’t have a market that performs like we’d hope it does. But we have a great belief in the economy. … When you deal with the market, it really all depends. Six months from now, it could be great.”

Naglick is not quite as optimistic.

Hear Naglick:“If you look at the year from July 1 to June 30, 2016, you’ll see that over that period the stock market didn’t do well so breaking even quite frankly might be an accomplishment,” he says.

Jeffrey Pegg, a PFRS trustee, says having the regular, future payments meant there was at least one steady stream of income to the funds. Under the terms of the bankruptcy settlements, the city is not making its large contributions until 2024, and Pegg says having the DIA and foundation contributions each year helped planning.

Hear Jeffrey Pegg“Now we’re not getting any more money in the legacy plans,” says Pegg, a 20-year veteran of the Detroit Fire Department. “Hopefully the market does well and we can make up that amount of money, that interest.”

Other Grand Bargain Money

Along with the state money and the DIA’s pledge, the grand bargain also had a $366 million commitment from a consortium of foundations, which are making annual payments to the city’s pension funds. Karen Chassin, a spokesperson for the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, which is administering the payments, says there are not currently plans to pre-pay any of those obligations. That means the pension funds can plan for continued $18.3 million payments each year. Two payments have been made: one in 2015, one this year.

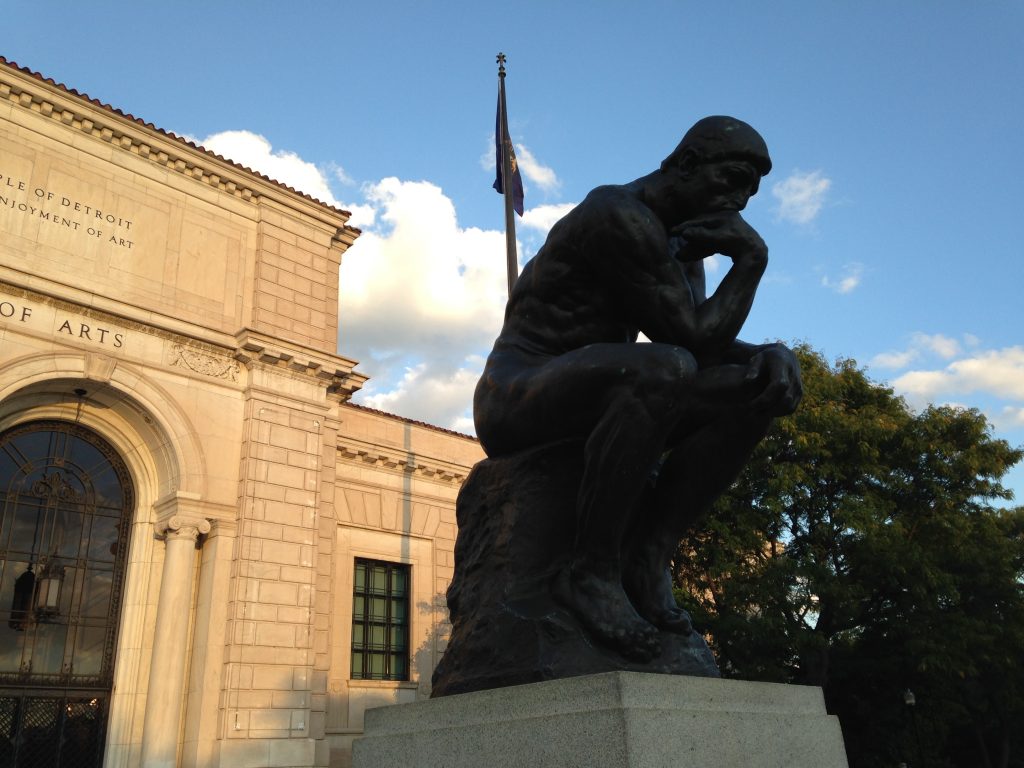

Constructed during the bankruptcy case proceedings, the grand bargain provided money to the pension funds along with a guarantee that artwork at the DIA would not be sold to pay creditors. Provisions of the deal, which was formalized through state law and the Chapter 9 case, also created the Financial Review Commission, a state panel overseeing city finances, and required new investment committees to oversee the pension funds.

“The grand bargain, as much as it was a unique approach to alleviating some of Detroit’s pension debt, did not completely eliminate risk from the pension system,” says Steve Malanga, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute who writes about public pension systems. “There remains risk in the Detroit system, and it’s exacerbated by the fact that post-bankruptcy, Detroit doesn’t have a lot of financial wiggle room.”

According to Malanga, Detroit’s presumed 6.75 percent rate of return on pension investments is typical for an investment that is highly unlikely to default, like 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds, which are currently around 4 percent.

“Detroit needs more than that to make its current setup work, but there’s no guarantee,” Malanga says. “As a way of comparison, some market gurus like Warren Buffett estimate that stock market returns over the next 10 years are likely to be lower than historical returns, maybe averaging just 6 percent.”

Hear Steve Malanga’s full conversation with WDET’s Sandra Svoboda here.

According to a report at Monday’s meeting of Detroit’s Financial Review Commission, the DIA did not prepay the full amount it committed to the pension funds. The museum has about $7 million of the original $100 million outstanding.

In 2015, the museum made a $5 million payment, meeting the terms of the 20-year payoff and leaving $95 million on the long-term balance sheet. Then last month, the museum made an early, one-time payment of $51.6 million — the discounted amount for $88 million of the total outstanding balance. It also made a $375,000 payment, representing the annual obligation for the roughly $7 million remaining under the terms of the bankruptcy.

DIA spokesperson Pam Marcil declined to comment to WDET about the reasons for the early payment. Last year, according to the Detroit Free Press, DIA officials announced the museum had reached the “present-day equivalent of its pledge to raise $100 million over 20 years” but “declined to release the exact amount that had been raised.”

Known donors to the DIA’s commitment include the Detroit Three automakers, Penske Corp., DTE Energy, Quicken Loans, Rock Ventures, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, Meijer, Toyota, Comerica Bank, J. Paul Getty Trust and the JP Morgan Chase and Mellon foundations.

According to a report at Monday’s Financial Review Commission, the DIA prepaid the equivalent of $4.625 million of its remaining $5 million annual obligations.