CuriosiD: Who Chooses Detroit’s “Tax-Free” Renaissance Zones?

Shelby Jouppi August 11, 2016Listener Paul wants to know – who chooses Detroit’s Renaissance Zones and what criteria do they use?

In this installment of CuriosiD, listener Paul Mungar asks …

Who are the deciding parties when it comes to choosing Renaissance Zones (in Detroit), and what criteria do they use to choose them? What is the history of Renaissance Zones?

– Paul Mungar, Ann Arbor

The short answer

What they are: Renaissance Zones are places in economically distressed cities where businesses don’t have to pay state and local property, income and utility taxes. The original zones included residential properties as well. The zones last for about 10-15 years. They aren’t completely “tax-free.”

Where they came from: The program was the 1996 brainchild of former Michigan Gov. John Engler.

How they’re chosen (in Detroit): The City of Detroit, the state and economic development groups work together to agree on boundaries for these zones. According to a former administrator of the city’s renaissance zones, in choosing the original six zones Detroit decisionmakers would look for areas of very low occupancy, light industry and few residential properties.

A great experiment

According to John Truscott, the then-press secretary to former Gov. John Engler, the Renaissance Zone program was an experiment. They wanted to see if eliminating as much of the tax burden as possible would encourage investors to redevelop certain areas of Michigan’s most economically hurting cities.

The state already had several incentive programs, like Neighborhood Enterprise Zones, but none that were so encompassing.

“We were looking for ways to take some of the worst dilapidated areas in our cities and kind of give them a kick start, see what we could do to get them redeveloped,” Truscott says. “Get interested investors to purchase property, redevelop it and hopefully get people to move in as a result.”

Many cities applied to participate in the program, and the state chose 11.

“We were looking for ways to take some of the worst dilapidated areas in our cities and kind of give them a kick start, see what we could do to get them redeveloped.”

Detroit was one of those cities, along with places like Grand Rapids, Flint, Pontiac and Benton Harbor.

“There were some requirements [for a renaissance zone]. It had to be property that had either been abandoned, was seriously dilapidated,” says Truscott. “It was property that was providing virtually no income for city.”

Truscott says there was pushback. The question from some: how could the state ask struggling municipalities to give up almost all tax income?

“And we felt we had an answer to that because these areas weren’t producing hardly any taxes anyway,” Truscott says. “And our promise to them was, if we work well together, do the right approach to this, in the end, you’ll have significant property that is now taxable.”

Choosing the boundaries

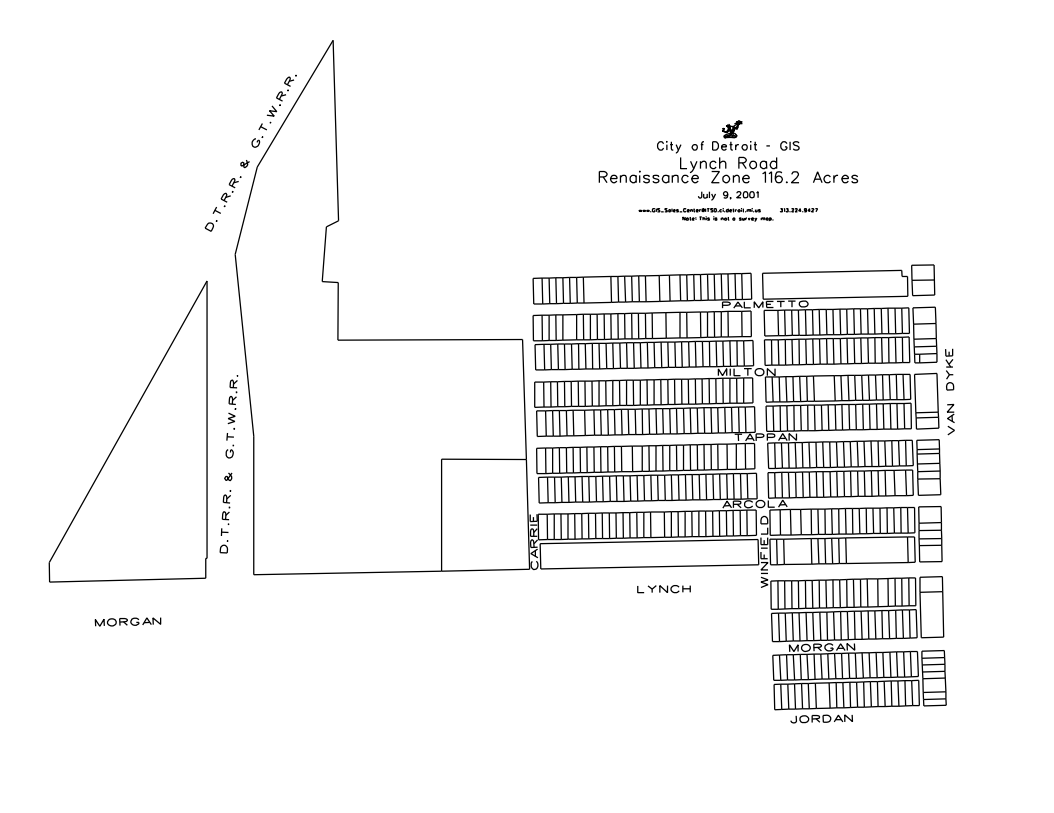

Below is a map of Detroit’s current and past renaissance zones as listed on the city’s website. You’ll notice that some boundaries seem to deliberately exclude certain properties, which begs the question: How are the boundaries chosen?

Note: This was recreated using the maps provided on detroitmi.gov as a visual guide.

The Decisionmakers

Jeremy Hendges is the chief deputy director of the Michigan Department of Talent and Economic Development, which houses the two state entities that oversee the Renaissance Zone program: the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Strategic Fund.

“It’s usually a collaborative process,” says Hendges. When it comes to Detroit, he says the state “usually will get something from, like, the DEGC (Detroit Economic Growth Corporation) … sometimes in conjunction with the city, sometimes they’ll hit us up first.”

It varies with each zone but ultimately conversations will transpire between the MEDC, the DEGC, the Mayor’s office, Detroit’s Planning and Development department and City Council.

In the end, for a zone to be created, the city must submit an application to the Michigan Strategic Fund, and City Council must pass a resolution supporting the zone.

Jill Babcock administered renaissance zones for the city from 1999 to 2004. She says in the beginning, it was rare for the city to create renaissance zones in conjunction with a particular business.

However, today, the most recently created zones in Detroit are business specific.

Sakthi Automotive was awarded renaissance-zone designation for the expansion of their Southwest Detroit campus. Auto supplier Flex-N-Gate has applied to the state for the creation of a next Michigan renaissance zone around the facility the company is building in the I-94 Industrial Park.

The Criteria

When it comes to the original zones designated in the 90s, Babcock says Detroit decisionmakers were looking for areas of extremely low occupancy and light industry because those are thought to be places where new businesses would have room to move in or existing businesses could expand.

“They avoided residential areas, however, some of the areas did become residential through the Renaissance Zone program,” Babcock says.

According to a Citizens Research Council of Michigan 1998 report on the Renaissance Zone program, its legislation stands out from other programs because, “zone boundaries need not respect established, bounded areas such as municipal borders or census tract.”

This gives lawmakers a lot of freedom when choosing the bounds of the zones.

Babcock describes Detroit economic developers as using that flexibility to their advantage.

“They did jerry-rig some of the zones, because, you know, why waive taxes – give a free gift – to an already established business? They didn’t need extra help,” she says.

As far as the criteria Detroit uses today in choosing the new zones, the Mayor’s office, the DEGC, and City Council have declined to comment.

Renaissance Zone poster child

Detroit Chassis is a kind of poster child for Detroit’s Renaissance Zone program. The assembler of motor home chassis built its plant in the Lynch Road Renaissance Zone of northeast Detroit in 1998.

“The renaissance zone was a critical part in comprising the package of assistance that the state was able to put together to induce us to make the decision to go Detroit rather than go Indiana,” says Detroit Chassis CEO Michael Guthrie.

His company was planning a multimillion dollar expansion. To attract Detroit Chassis to spend that money in Detroit rather than Indiana, the state worked with Guthrie, the city, Wayne County and Ford Motor Co. to form an incentive package.

Guthrie estimates the company is saving about $400,000 a year in taxes.

“The additional cost of doing business here can be considerable for some companies,” Guthrie says. “The lack of city services, at the time for example. There have been times where we’ve hired our own plow trucks, we’ve had to provide extraordinary security. We’ve had to provide extraordinary support to our employees.”

Detroit Chassis worked with the state to employ over 100 people who are “difficult to employ.” Guthrie says the company has had a full-time social worker on staff for the past 15 years as well as a company chaplain.

Guthrie says Detroit Chassis employs 240 Detroit residents.

Lynch Road Renaissance Zone – 20 years later

Half of the Lynch Road Renaissance Zone consisted of residential properties. When the original renaissance zone designation expired in 2008 — smack-dab in the middle of the Great Recession — Detroit Chassis approached the city and state for a new renaissance zone agreement. But it didn’t include the residential streets.

Patricia Bosch, executive director of Nortown Community Development Corp., says she doesn’t think the program benefited the community as promised.

“It benefits the business, and that’s a good thing. We’re not opposed to that,” she says. “We are pro-business and pro-economic development, but it can also work two ways. And reading the literature on renaissance zones, it is supposed to benefit the residential as well and I believe that’s the great disconnect that’s happened in District 3.”

Karen Washington, another northeast Detroit community development administrator, says she and Bosch didn’t know the original zone included residential streets. She thinks the residents were unaware as well.

“Awareness has been a big part of what does not happen at the community level,” she says.

“Awareness has been a big part of what does not happen at the community level,” says Washington.

Bosch says the occupancy of the Lynch Road Renaissance Zone has remained more or less the same. Forty-five new single family homes were developed as part of a low-income housing program, but she doesn’t know if that was because of the Renaissance Zone program. She thinks together with the city, the community could have made some strides redeveloping the section of Van Dyke Avenue included in the zone if there had been more cooperation.

“The city should have been working hand-in-hand with us in order to do more development along that zone,” Bosch says.

Former Detroit Renaissance Zone administrator Jill Babcock says the city and the DEGC did conduct outreach in the Lynch Road neighborhood. She says her phone number was on the city’s tax form and that she responded to every inquiry.

How successful are renaissance zones?

Truscott, the former press secretary for Gov. Engler, refers to the Renaissance Zone program as a big “experiment.” Engler’s administration wanted to see if eliminating taxes would ignite economic development in the state’s worst areas.

True experiments involve analysis. But sources at the city and state could not provide any formal evaluation of the program’s success over time.

So what is the exact worth of renaissance zones in Detroit?

After 20 years, no one knows.

The asker

Paul Mungar grew up in Detroit’s Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood. He’s been a community activist and artist in the Detroit area for decades. Mungar says he’s seen first-hand the effect pollution has had on the residents of Detroit’s most heavy industry areas – like Delray and River Rouge. He says his family members struggle with severe illness as a result.

He was doing some personal research when he found that the Marathon Petroleum Company’s Detroit refinery hadn’t been paying property taxes for years because its facility was in a renaissance zone.

That’s what inspired his question.

“I’ve been interested in acquiring property and not having to pay taxes because what I was doing on the property was a communal effort … and make a positive impact and actually increase the value of the land.” Mungar says. “That seems like something that should be delegated tax-free status, not something that’s pumping pollution into the air.”