Detroit Journalists Risked Their Lives Covering 1967 Unrest

Erik Smith, Gene Elzy and Jerry Hodak saw their lives changed by the events of July 1967.

Members of Detroit’s media corps risked their lives in July 1967 to cover perhaps the city’s most important story of the 20th Century. Their reports shaped the initial images most Detroiters had of that summer’s civil unrest. For the journalists though, the events created life-long memories.

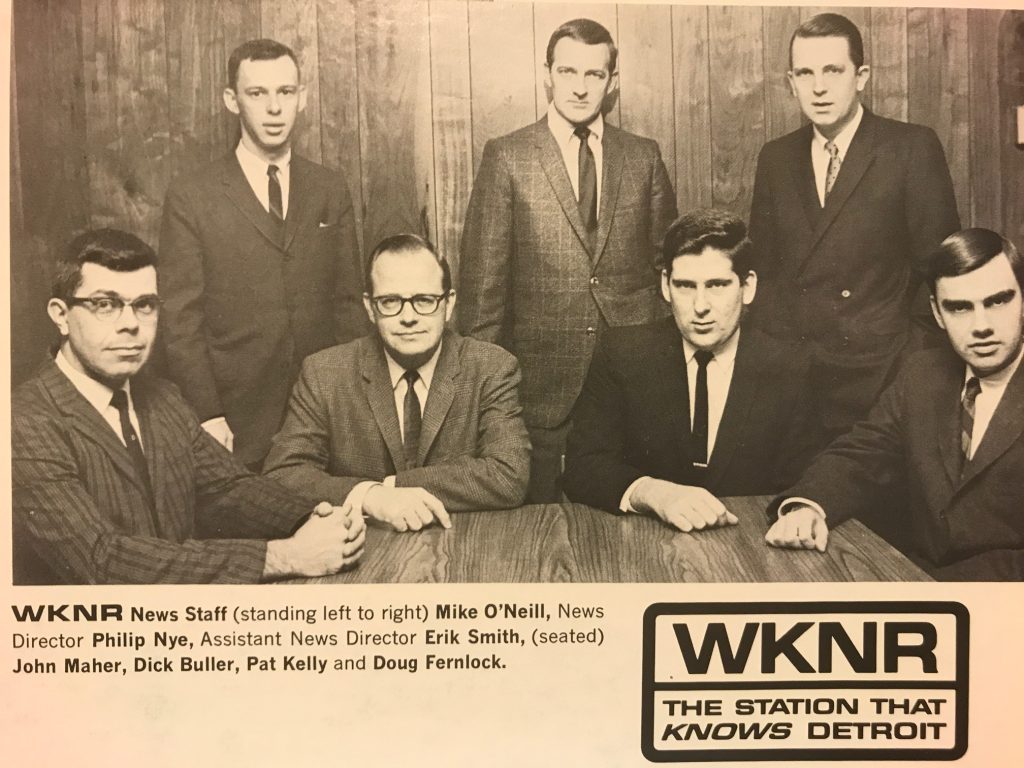

No one in Detroit knew in late-July 1967 that the city was just a few days away from an event that would make history. School was out, teenagers were listening to rock ‘n’ roll on WKNR and rhythm and blues on WCHB. Around town, television reporters were covering stories like the marital problems of Mayor Jerry Cavanagh, and the Tigers’ efforts to win their first pennant in decades. Detroiters had watched national news coverage of the riots in Newark earlier in the month, but the common refrain in town was that the same thing couldn’t happen here. Erik Smith says he’ll never forget first hearing about the disturbance at 12th and Clairmount. He was the assistant news director at WKNR radio at the time.

“I remember it distinctly,” says Smith. “You can’t not remember it. It’s one of those days that, much like the Kennedy assassination, you remember that moment in time. And it was July 23rd. We had, my wife and I, had gotten up early that morning because we had plans to go out to Kensington Park with some friends for a picnic.

“And I got a telephone call from one of the guys at the radio station”, says Smith. ”’Something’s going on down on 12th Street,’ he said. ‘Nobody’ll talk,’ he said, ‘but they’re sending in the tactical mobile units.””

Gene Elzy was WCHB’s news director in July 1967. He first heard the news during an early morning phone call from his boss.

“It was Dr. Wendell Cox, one of the owners of WCHB,” Elzy says. “I was the only news person at that moment. But Dr. Cox called me early that morning and said, ‘They are rioting on 12th Street, and you need to get down there. There will be in another hour or so, there will be a meeting at the police precinct on Livernois.'”

But most Detroiters still didn’t know anything was wrong, because city officials had convinced the media to keep a news blackout until Sunday afternoon. WKNR’s Erik Smith says,”The news was being controlled by the power structure, from city hall to the police department.”

“That morning, it was very hard to get any information. We could not get any information. My memory is that either city hall or the police department or both asked us, the media in general, to keep a lid on it; don’t talk about riot, don’t say there’s a riot in progress, don’t use inflammatory expressions. Let us try and get a handle on it.” — Erik Smith

But by the time that meeting was over, the situation was already out of control. Gene Elzy drove to the riot’s epicenter to get a good look for himself.

He says, “When I got into the area, in general, people were running all over the place.”

“People were throwing things through windows, trash cans and bricks and pulling the security fences off of the storefronts. It was just a madhouse, I mean it was really a madhouse, and it was something that was frightening.” — Gene Elzy

Meanwhile, Erik Smith drove up Grand River Ave. to get an idea of what was going on there. He wasn’t prepared for what happened next.

“I was recording some of this on a tape recorder, just the sounds of the turbulence in the street,” Smith remembers. “And a red light flashed at Joy Road. I was right by the Riviera Theater there at Joy and Grand River. And I stopped for a red light. All this lawlessness is going on about me and I stop for a red light. And unfortunately I was spotted by a group of very angry people in the crowd. And they surrounded my car and began rocking the car and turned it up on its side. They did not attempt to harm me. I got out of the car and began running.”

Governor George Romney called out the National Guard Sunday night, but the civil unrest continued to escalate. Meanwhile, radio and television stations were warning their personnel to prepare to work around the clock. Jerry Hodak, normally the weatherman on WJBK Channel 2, was pressed into full time service as a reporter.

“Well, eventually a curfew was put into effect. As of sunset, everybody had to be off the streets,” Hodak says.

“I think what was most impressive to me was just driving along the John Lodge Feeway or the Edsel Ford Freeway and not seeing another car anywhere in sight. It’s like there was a nuclear holocaust and everybody had been wiped out and you were the only people left on earth. Except for the fact that you heard all this noise in the background and you could see the fires burning.”

As parts of the city burned, Detroit’s black radio stations tried to calm listeners living in the neighborhoods in revolt. Jay Butler worked the afternoon shift at WCHB. He remembers Martha Jean “the Queen” Steinberg’s marathon broadcast on WJLB and her efforts to get rioters off the streets.

“After it got so bad, people were, I think there were something like five people that had gotten killed at some point in time,” says Butler. “And then they brought in the National Guard. ‘The Queen’ stayed up for that whole day, that whole day and night. I remember the broadcast telling people to stay in, to stay off the streets, to stop rioting, and she did that for at least 24 hours. And it is sad to some degree that she had a lot to do with, kind of, quelling the disturbance that was going on.”

But looters, black and white, continued to roam the streets. National Guardsmen escorted fire crews after one fireman was shot to death and others were pinned down by snipers. Erik Smith says sections of the city were simply in chaos.

“Walter Reuther called them the days of madness,” says Smith. “And I don’t think I’ve ever heard a better description of what I saw and what I felt and what I lived through in those four or five days. I’ve often said they were the worst days of my life.”

By Monday, the civil disturbance had spread to the city’s east side, as well as north along Livernois Ave., and city officials saw no end in sight. Gov. Romney asked President Lyndon Johnson to send federal troops into Detroit.

“As governor of the state of Michigan I do hereby officially request the immediate deployment of federal troops into Michigan to assist state and local authorities in re-establishing law and order in the city of Detroit. I am joined in this request by Jerome P. Cavanaugh, mayor of the city of Detroit.” — Gov. George Romney

National Guardsmen were already patrolling the city. WKNR assistant news director Erik Smith recalls the scene.

“Here I am, 24-years old, watching United States military tanks rumble down West Grand Boulevard in front of Henry Ford Hospital,’ says Smith. “That picture is indelibly impressed in my mind because I thought to myself, I am a civilian, standing in the city of Detroit, watching U.S. military hardware rumble down the streets, watching a 50 caliber machine gun open fire on an apartment building. I was in war.”

Just a few blocks from Smith’s location, his boss, WKNR News Director Philip Nye, crouched in the shadow of the General Motors building to report on the chaos.

Nye said this in his broadcast: “This area, full of snipers tonight, the vehicle sounds in the background, are the tanks, armored personnel carriers. [shot in the distance] That would sound more like a sniper shot, the ones we’ve just heard. [sounds of repeated gunshots, followed by explosion . . . Nye tries to speak but voice is inaudible among the noise] Apparently moving more troops in. I’m looking up now. A truck, a trooper is coming in [continued gunshots, explosions] . . . this occurred just as we moved down from the 12th and Euclid area where we were in with the guard. Four casualties had to be moved out there [explosion]. And that’s the sound you’re hearing all over Detroit this evening.”

As the gun battles continued throughout the city, journalists tried to stay out of the line of fire while filing their reports. But for the city’s black broadcasters, just trying to get to work was a harrowing experience. WCHB News Director Gene Elzy knew he would be on the streets during the curfew, so he prepared himself by placing his press pass and his driver’s license on the dashboard of his car. He drove straight down the center of Livernois with both hands visible on the steering wheel. But he still wasn’t prepared for his meeting with a group of guardsmen.

“As I approached Davison, it got really scary because I could see in front of me National Guard troops,” Elzy says. “They spread out all the way across the street from sidewalk to sidewalk. I approached them, I slowed, they began to level their guns at me. They converged on both sides of the car, in front of the car, there were those behind the car, all with rifles pointed at me. And I said, ‘I am a newscaster, here is my press pass and my driver’s license,’ always careful to keep my hands up. They just continued to holler and scream and you could here the bolt action of the rifles as they were putting shells into place in those rifles. I thought I would die.”

But Elzy managed to keep his cool, despite the danger that stared him in the face.

“They went through my clothing, they went through the trunk of the car, they pulled everything out of the trunk,” Elzy says. “After they did all of this, they looked at the press pass, and they looked at the driver’s license, and they said simply, ‘OK, you can go.’ And I thought, you know, why would you do this to me? I’ve got proof, but they began to move on, still in this flying wedge, past me and on up the street. I had to pick up all the stuff and put it back in the car. This thing just unnerved me. I mean, as I think about it now, it unnerves me, because it frightened me beyond belief.”

Abuse of black Detroiters was common and merely fueled the anger that originally had led to the riot. A few miles away from where Elzy was stopped, Erik Smith received his own lesson in race relations from a Detroit police officer.

“I saw a 16-year old boy. He was taking a television set,” Smith says. “Highland Appliance used to have a warehouse building on the corner of, I think it was Grand River and Ford Expressway. I pulled up and saw this youngster, he might have been 15, 16 years old, darting out from the building down this alleyway carrying a television set. And a Detroit cop, who was there in the alley, and he yelled at that kid, ‘Stop!’ And the kid kept running and he said, ‘Stop, or I’ll shoot!’ And he shot that kid with a shotgun. I saw him fly up in the air, the television set go flying. It was a child. A child – for a television set!”

By Friday, July 28, most of the fires had been put out, and the soldiers began packing up to leave town. Reporters caught up on their sleep and then began asking some tough questions, mostly of themselves. WJBK’s Jerry Hodak says, “I don’t see how it could not change somebody. I think it changed me as a human being. It had to. If it didn’t, then heaven help you. I think from one standpoint as a journalist suddenly, we went from covering ribbon cuttings to covering essentially what was a war. And then there was the underlying social issues that had to be dealt with. And, how did this happen? How did we allow it to happen? Is there something that we should have been doing that we didn’t do? We began to become very introspective about what we were portraying on television for a lot of years. Were we giving a picture of our city that was an accurate one? I mean we began to ask ourselves a lot of questions – with good reason.”

The official final toll: 43 dead. 467 injured. 2,500 stores looted or burned. And an estimated $80 million in damage. Detroit was changed forever.

(This story was originally aired in July 2001.)