Stunned by Violence, Detroit Tigers Players Worked to Restore Peace in July 1967

The Tigers were in midst of a tight race for the pennant in July 1967.

Editor’s note: John Farrup filed this story for WDET in 2007.

In 1967, the Detroit Tigers were primed for a run at the World Series. Pitchers Mickey Lolich and Denny McLain and hitters Al Kaline, Willie Horton, and Norm Cash were big-time ballplayers. Soon, they would mean much more than that.

On July 23, the Tigers were chasing the Chicago White Sox, the Boston Red Sox, and the California Angels in the American League pennant race. That Sunday, they split a doubleheader against the New York Yankees at Tiger Stadium. Legendary broadcaster Ernie Harwell recalled that fateful day.

“When I got through the game, I went out to the parking lot where the Tigers and the players and the executives and workers parked,” Harwell recalls. “And a policeman said, ‘How are you going home? There have been some problems.’ And I said, ‘I’m going up Jefferson.’ He said, ‘Well just keep going, don’t stop because people are rioting and it’s a little dangerous.’”

While Harwell was up in the broadcast booth, pitcher Denny McLain was in the dugout. Both teams were observing an unusual sight just north of the ballpark. Five miles away, the situation at 12th street and Clairmount was spiraling out of control.

“Well, we saw the smoke coming up over the – over the left field deck,” McLain says. “The entire game we saw the smoke. No one knew what it was. (General Manager) Jim Campbell of course had put the kibosh on telling anybody in the stadium. He told everybody that had anything to do – anybody with knowledge of what was going on north of the ballpark that they weren’t supposed to say anything. ‘Don’t tell the crowd, don’t panic the crowd, don’t panic the players, don’t do anything like that. Let’s get the doubleheader in and move on from there’, so we were totally unaware.”

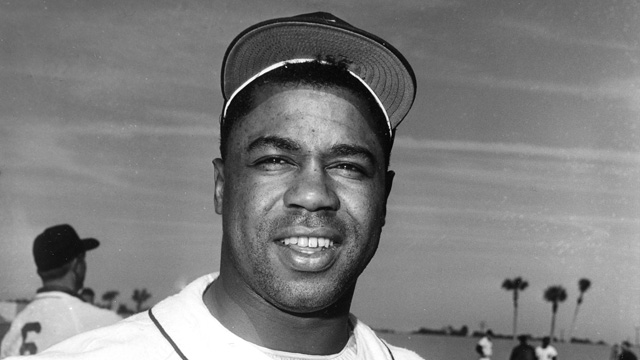

As Harwell and McLain left the stadium for their suburban homes, Tigers’ slugger Willie Horton was driving right into the heart of the disturbance. He lived just a few blocks away from the epicenter of the riot.

“I didn’t know what was – quite what was going on myself. All I know is it looked like it was a war,” Horton says. “You know, you see a lot of red burning and stuff…and I’m just trying to think about…Doctor King. He died for opportunity. He was all (about) opportunity.”

Seizing that opportunity, Horton, still wearing his Tigers’ uniform, climbed the hood on top of his car and pleaded with the crowd for peace.

“It was just like yesterday to me really,” Horton says. “Just like shutting my eyes, I can see myself on the car and I’m out there in the middle of the riot getting on top of my car trying to bring peace to the people.”

The uprising had grown in intensity and Horton was unable to quell the mob. Instead, neighbors told him to leave so he wouldn’t get hurt. Tigers’ outfielder Gates Brown lived in an apartment within earshot of where Horton stood.

“I mean, I’m seeing people running down the street with couches over their heads, chairs, stealing and breaking into stores,” Brown says. “And I also see store owners with chairs standing in front of their businesses with shotguns…protecting their business, too. I was there, I was in the middle of it.”

Danny McLain made it home safely to Bingham Farms that night, but stayed glued to the television and radio. He says news outlets made it sound like the violence could easily spread into the surrounding suburban areas. He prepared accordingly.

“I know that night or the next couple of nights, you know, we all stayed at home,” McLain says. “I had relatives in from out of town that weekend, and we stayed up all night Sunday and Monday night with guns in our laps. We didn’t know how bad it was going to be because there were so many horrible, horrible radio rumors. You know, ‘they’re moving to the country or they’re going out to the suburbs. Guys with guns have been spotted going out on the John Lodge (Freeway).'”

While race relations were at a crisis point in the city, many players from the Tigers’ organization say race in the clubhouse was not an issue during that time. Willie Horton says that a majority of the players from that era still stay in contact with each other.

“We didn’t have a problem,” Horton says. “We had very black and white guys that understood each other, and I don’t think person we ever looked at the color of their skin. We did a lot of things to get each other home and when we travel.”

Denny McLain shares that sentiment.

“I went to school on the south side of Chicago. I can tell you about racism,” McLain says. “There weren’t many guys that came to the major leagues that came from the background I came from on the south side of Chicago. What I saw in our clubhouse was hardly racist.”

That clubhouse harmony existed despite the fact that the Tigers’ organization was not historically a cornerstone of racial equality. Walter Briggs, who owned the team from 1935 to 1952, refused to allow black players on the team. A Dominican ballplayer, Ozzie Virgil, Sr., was the first black player to don a Detroit uniform in 1958. A year later, the team signed its first African-American player, Larry Doby. And in 1961, Jake Wood, Jr. was the first African-American player from the Tigers’ minor league system to join the big club. For years, black baseball fans weren’t allowed to sit in the box seats at Tiger Stadium. Gates Brown says that the legacy of racism in the sport has had an impact on the city.

“Even to this day you hear of the old time black people say things – derogatory things — that Walter Briggs said about blacks,” You find a whole lot of black folks that aren’t too particularly keen on the Detroit Tigers, just because of that.”

The day after the riot began, Brown and the Tigers took to the road for an extended 15-day trip. When they returned, several players ventured out into the city to assist in the healing process, by working with kids at baseball parks and speaking at community functions. For the rest of the summer, the team would continue to grind it out in the competitive American League. In September, the race was close.

“Eventually, it came down to the Tigers and Minnesota (Twins) and the Boston Red Sox,” Ernie Harwell recalls. “And the Tigers lost on the last day when (Dick) McAuliffe hit it into a double play. The Red Sox had already beaten Minnesota at Fenway (Park), and they were listening to the radio, our account of the game, and heard about that, and then they were able to celebrate their 1967 pennant. But the Tigers were in it and had a good chance, the problem was they ran into doubleheaders. If they had done better than splitting those two doubleheaders, it would have been a different story.”

The Tigers finished in second place in the A.L., one game behind Boston, which lost the 1967 World Series to the National League champion St. Louis Cardinals. Detroit won the A.L. pennant in 1968, and beat the Cards in the World Series. Denny McLain won the A.L. Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards that season.

Where are they now? Ernie Harwell died in 2010. Gates Brown died in 2013. Willie Horton works for the Tigers, as a special assistant to General Manager Al Avila. In 1994, McLain and other investors bought a meat packing plant. Two years later, he was convicted of embezzling money from an employee pension fund. He spent six years in prison. He hosts a weekly show on another Detroit radio station. Tiger Stadium was demolished in 2009. The Detroit Police Athletic League is building a new youth baseball field at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull.