Could Blockchain revolutionize government record keeping?

A new digital ledger technology could be the answer to transparent government and record keeping.

Imagine being able to check all public records on a real-time ledger. Any citizen could verify acceptance of paid utilities the minute the transaction is accepted. Anyone could see property ownership records without the need to FOIA. Residents could see in real-time money going in and out of Detroit’s demolition program. And residents could check this information at any time from their home computer.

How?

On a blockchain.

What is Blockchain?

The blockchain is a digital bookkeeping ledger technology designed to be 100 percent transparent and 100 percent immutable.

It’s a secure, decentralized, internet-based record of all transactions logged on to it.

Some experts have said that it could solve issues in government such as transparency and accountability.

Pamela Morgan explains one example it can do this is keeping track of government tax spending. Morgan is the founder of the Chicago-based law firm, Empowered Law, which focuses on digital currencies and blockchains. She’s also the founder of the crypto-asset consulting company Third-Key Solutions.

“In a perfect world we would be able to track all tax collection expenditures and we would actually be able to see where our tax dollars are going as a whole,” Morgan says.

Right now, citizens get tax-spending reports from auditors. They are the ones with access to financial records from our local governments.

They get to see the books. Citizens don’t. The books can be requested by Freedom of Information Act or FOIA. But that process could sometimes take days or weeks.

But if each tax dollar spent was recorded on an immutable ledger that was public to everyone, Pamela Morgan says there would no longer be a need for third-party auditors.

“All of the transactions are transparent and available,” Morgan says.

The blockchain IS the record. Instead of getting audits, citizens could see when money is spent the minute the transaction is made.

Morgan says blockchain could also help keep track of water bill payments, which could be helpful in Detroit.

“If we could have the water company adopt some sort of open public blockchain, anyone would be able to prove instantaneously without going through the records department, or the billing department, or having to submit your bank records to prove that you actually paid these things,” Morgan says. “They can look it up online without you having to interact with their system at all. Because their system is your system. It’s our system.”

This digital bookkeeping ledger technology makes it possible for all citizens using the software to have instant access to the information filed.

How does it work?

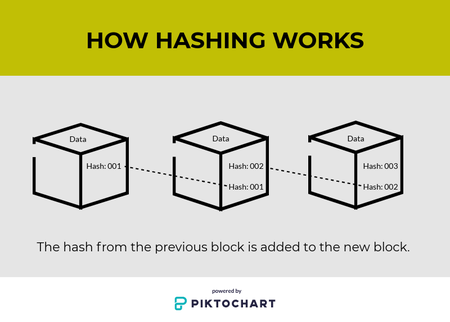

The Blockchain is a list of transactions. Each transaction is recorded onto a block and the blocks are linked together through hashes.

A hash is essentially a thumbprint of a transaction. Each block has a thumbprint of the previous block on it.

To change that block, you must also change the thumbprint. To change the thumbprint, you have to change the block before it…and the one the before that, and the one before that, and so on. Each block is connected.

This may not be too much of a hassle for a hacker. But, the blockchain is public and everyone participating in the network has a copy of that ledger. Blocks can only be added on to the chain once they are verified by everyone with access to the chain.

So, a hacker doesn’t just have to hack one computer. They would have to hack all the computers on the chain. This makes the chain immutable. Information is not just kept in one place — it’s shared by everyone.

“One of the interesting things about blockchain is the idea of decentralization,” Morgan says. “So, we stop having centralized repositories of this information.”

How can we use it?

Keeping digital records isn’t new. But the ability to give everyone instant access to that record is.

The ledger could be used for different functions of government. Imagine being able to purchase property in Detroit and the deed you own carries around with it an immutable record of how the property came into your possession.

A blockchain keeping track of that information in the Register of Deeds office could make that possible.

“Instead of having the register of deeds where you physically go and you have this piece of paper and they stamp it and they record it in the grantor/grantee index,” Morgan says. “Instead of having that, basically the grantor/grantee index is available as a public record. But an unalterable public record, in real-time, instantaneously.”

With a blockchain in place, there wouldn’t be a need to argue whether you own a property. The proof is in the ledger.

Other governments around the world are dabbling in this new technology. In Ghana, West Africa, a land registry built on a blockchain is being implemented in communities to create “tamper-resistant property ownerships.”

Sweden’s government is planning to place all real-estate transactions on a blockchain so all parties involved can track dealings.

And in the U.S., Cook County, Illinois introduced a pilot program to see if there are any legal ramifications to using a blockchain to keep track of land registries.

“That’s one good thing that blockchains are about. One thing they can do is really have a transition to paperless government.” – John Mirkovic, Deputy Recorder of Deeds, Cook County, Illinois.

Cook County Deputy Recorder of Deeds, John Mirkovic, says researchers found that doing so is completely legal, and feasible and the department created hashes for all land properties in the county so that it could easily be transferred to a digital ledger. There isn’t a blockchain in place yet for land records in the county. But they are now one step closer to making it a reality.

“It solves a really big problem in government’s record processing in general. It doesn’t have to be land records it can be medical records, it can be car title records,” Mirkovic says.

Right now, when a property is sold the transaction must be conveyed by lawyers, the land registry, and others. That’s multiple people copying and re-copying…filing and re-filing the sale. Mirkovic says government clerks having to recopy information for various departments allows errors to pop-up.

“You have inaccuracies that come into the public record that can really be solved if we unified the actual act with conveying the property with the information that was used to create it,” Mirkovic says. “That’s one good thing that blockchains are about. One thing they can do is really have a transition to paperless government.”

Should we use it?

Blockchains are still a new technology. So, there is still a need to be cautious about how to use it.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s chief technology officer for Connection Science, Thomas Hardjono, says before governments decide to use blockchain technology, they must first decide what information citizens have rights to.

“It’s a data access, data privacy question at this point,” Hardjono says. “For example, if I purchase a house in Detroit. This is a transaction between me and the seller. Should that fact be made public? If so, to what degree?”

Hardjono also says that the Equifax data breach brings up the question of co-ownership rights between a person and government or company with access to that data.

“You need to sit down and figure out if you are a local government, what types of data do you have about citizens there, about taxpayers there. What type of data do you have about the government itself?” Hardjono says.

So maybe sensitive material like medical records, or even voting processes, should not be placed on blockchains.

But other government records like tax spending, which are supposed to be public, can.

And Pamela Morgan says that can be very powerful.

“I think it changes the way we can hold our governments accountable and our elected officials accountable,” Morgan says. “But I think it also changes the way that they operate and do business.”

Morgan says there is always a bit of risk when testing out new technology. But if the current system is broken–and she would argue it is–a little bit of risk is worth making a change.