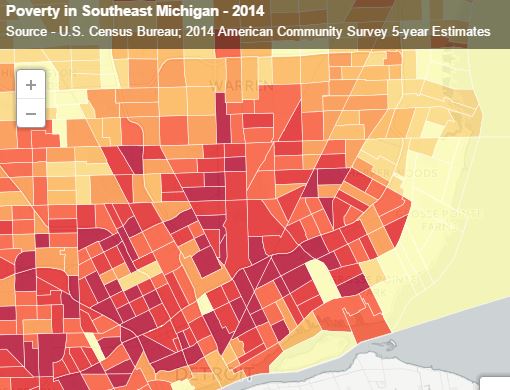

The Intersection: The Persistence of Poverty [MAP, CHARTS]

The problems of poverty are bigger than the programs, policies designed to solve them.

When the Kerner Commission Report came out in 1968 to explain the wave of urban violence across the country, its authors famously warned that America was headed toward two societies, separate and unequal, largely based on race.

Now family income also is defining inequality in urban America, where most of the biggest cities saw rises in the percentage of people living in poverty between the 1960s and today.

The problems of the resulting poverty are bigger than the programs and policies designed to solve them, says Liette Gidlow, associate professor of history at Wayne State University.

“There are broad economic forces at work: globalization, decline of manufacturing. The jobs that have been created in the last several decades that have replaced manufacturing jobs have not replaced the incomes earned by those jobs,” she says. “Even the minimum wage has not kept up. So incomes are down over time, and the result of that is increasing poverty.”

In Michigan cities, the story is more dramatic than in the rest of the country. In the state’s 12 biggest municipalities, the percentage of people living in poverty rose dramatically during the last five decades. In 1970, 15 percent of Detroit residents lived at or below the federal poverty line. By 2014 that had nearly tripled and is the nation’s highest among big cities.

| 1970 | 2000 | 2014 | |

| Detroit | 14.9% | 26.1% | 39.8% |

| Ann Arbor | 11.8% | 16.6% | 22.6% |

| Dearborn | 5.6% | 16.1% | 28.6% |

| Flint | 12.4% | 26.4% | 41.6% |

| Grand Rapids | 12.5% | 15.7% | 26.7% |

| Kalamazoo | 14.6% | 24.3% | 35.0% |

| Lansing | 10.1% | 16.9% | 29.4% |

| Livonia | 2.1% | 3.2% | 6.1% |

| Pontiac | 13.3% | 22.1% | 37.8% |

| Saginaw | 26.3% | 28.5% | 35.5% |

| Sterling Heights | 2.9% | 5.2% | 13.0% |

| Warren | 3.3% | 12.4% | 19.6% |

“Detroit is an outlier in the extent of poverty relative to the other major cities here in the United States that it’s up against,” says Matthew Larson, assistant professor of criminal justice at Wayne State University.

Throughout the state, the effects of poverty are widespread and felt differently in each community, says Kate White, executive director of Michigan Community Action, a network of organizations throughout the state that seek to reduce poverty by increasing family earnings and self sufficiency and creating community partnerships between individuals and organizations.

For example, the lack of mass transit in the Detroit metropolitan area means people without cars can’t get to jobs. In some smaller, more rural Michigan towns, when a main employer leaves, the impact is greater than in a metropolitan area. If a city or suburb’s rental homes are not energy efficient, have lead paint, or are expensive to heat, family budgets are affected differently, White says.

“Poverty shows its face in many, many ways,” she says. “If people are struggling to keep a roof over their head, that means less money for food, less money for extras.”

The cycle of poverty, then, travels through other sectors. In Detroit, being poor contributes to public safety as a top priority for the city. Indeed the city’s crime rate eclipses other American cities.

Detroit Police Assistant Chief Steve Dolunt agrees it’s often the income challenges for individual citizens that become public safety challenges for communities.

“You’ve got to eat. If you don’t have money, you’re going to find ways to make money, and you can make money quicker selling drugs or breaking into people’s houses or just sticking up someone on the street,” Dolunt says. “You have to understand the plight of the impoverished.”

Many of the efforts to reduce poverty in Detroit and other cities have been simultaneously led, influenced and stifled by the federal government, Gidlow says. That dynamic starts with who is in the White House and dates back to the beginnings of the Republic.

“We had the Jeffersonians and we had the Whigs, or the Federalists and the anti-Federalists,” she says. “Some believed in internal improvements, that is in funding basically public infrastructure, public works, resources that would help to develop areas economically, and others that had a different vision, a more agrarian vision.”

Just a few years before the urban uprisings of the later 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson declared his “War on Poverty,” a part of his Great Society programs.

“He laid out a vision for a society that could address problems of poverty and joblessness and lack of education and lack of access to health care,” Gidlow says. “He thought that this society could do better.”

Johnson’s efforts eventually led to Medicare and Medicaid, food stamps, jobs programs and a network of Community Action agencies, which remain in place. Michigan Community Action and its 29 affiliates are a legacy of that work.

“They’ve survived to this day because they’ve continued to evolve,” White says.

But Gidlow says at the time when community action agencies formed, conservatives especially blamed them for the urban riots of the 1960s.

“There are some who felt that these Community Action Agencies helped radicals to organize and that federal dollars were being used to attack the status quo,” she says. “There were some people who felt that these were bad actors and that they were being funded by the federal government and felt that that was inappropriate.”

The Nixon Administration dismantled some programs, including the Office of Economic Opportunity, which Johnson had created and then tried to use to prevent urban unrest by improving conditions in cities, Gidlow says. Under Ronald Reagan, some of the funding that had gone to federal anti-poverty programs transformed to the Community Development Block Grant program and were reduced.

“Jobs as a political issue, is something that has been very controversial through most of the 20th century up to our own day,” Gidlow says.

But poverty rates in cities remain high and unmoving. White defends government- and nonprofit-led efforts to address root causes of poverty in Michigan, saying the reasons for poverty are too complex, widespread and not able to be anticipated or controlled.

She cites 20 years of stagnating wages, outsourcing of “massive amounts of jobs,” lack of investment in education, the state’s failure to change how schools are funded, low high school graduation rates, cuts to mental health services, epidemics in substance abuse and “criminal justice reforms that went too far” with incarcerations for non-violent crimes.

“All of these things in combination have really made it virtually impossible to solve poverty,” White says. “The problems are so intense, and there are so many people in difficult straits that it’s going to take a lot of time and a lot of strategic thinking to pull the resources together.”