Of Myths and Men: When the Tigers Didn’t Save Detroit

New book puts 1968 World Series triumph in perspective

When the Detroit Tigers won the World Series in 1968, many considered it a godsend to a city that was scarred by deadly violence the year before. It was thought that a championship would help heal those scars and unite Detroiters, who poured out of office buildings and onto the streets to celebrate moments after the Tigers vanquished the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games.

Fifty years later, the summer of ’68 still holds a special place in Detroit’s history and its collective memory. Mickey Lolich, who pitched three games against the Cards and was named the World Series’ most valuable player, threw out the ceremonial first pitch on Opening Day 2018 at Comerica Park. He recalls stories told by police officers who greeted players at Tiger Stadium.

“In ’67, you’d see three or four guys standing on a street corner looking for trouble. ’68, you’d see the same guys on the corner, with transistor radios listening to Tiger games,” Lolich says. “They said, ‘you guys really made a big difference to what happened in the city in 1968.'”

Mickey Lolich believes that. Sridhar Pappu wants to believe it.

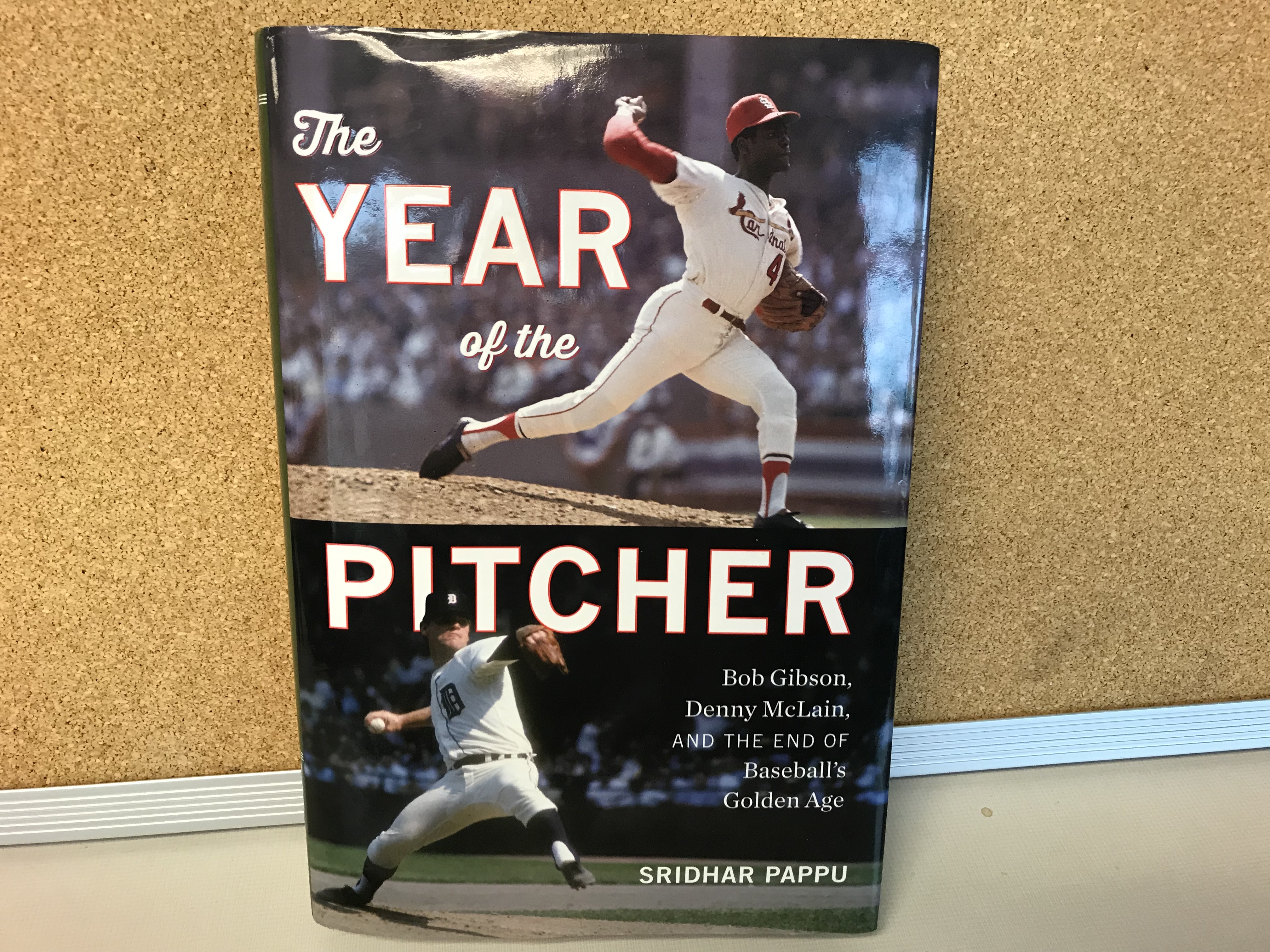

“Unfortunately, it’s just not true,” Pappu says. He explains why in his new book, “The Year of the Pitcher: Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, and the End of Baseball’s Golden Age.”

Pappu is a columnist for the New York Times. He spent five years doing research for the book, which covers a lot of bases. While the myth of the ’68 Tigers lifting Detroit’s weary spirits still has life a half-century later, he emphasizes that it’s just that–a myth.

“If you look at what was going on in Detroit in 1968, you saw the ascendancy of George Wallace‘s presidential run in the white wards of the city,” Pappu says. Wallace, the former Alabama governor, ran a third-party campaign for the White House that year, on a pro-segregation platform that appealed to working-class white voters. He won 10 percent of the popular vote in Michigan, and won the state’s Democratic Party primary election in 1972. Pappu rejects the notion that the ’68 Tigers had the power to suddenly heal racial divisions that had left several blocks of the city in ruins the year before.

“(It) puts a tremendous onus on a baseball team as they’re trying to do their job,” Pappu says. “The feelings that helped spark the riot, the conditions that existed were still present, and I think it was important for me to unpack that myth.”

“The Year of the Pitcher” also gives readers an intimate look into the early lives and careers of its central figures: Bob Gibson and Denny McLain. Pappu also writes about the national pastime’s own existential crisis in 1968, the offensive struggles of its hitters, and its failure to keep pace with a quickly-changing social, political, and sports landscape.

Click on the audio player to hear the conversation with WDET’s Pat Batcheller.